Cover image PamplePaperStudio

With the arrival of Spring and my Angel Wing Begonia shooting its first pink flowers of the year, it was only a matter of time before the crazy plant lady I am decided to write an article about botany in the arts.

Watering my 80+ plants often resembles a 1h30 meditation session during which I prune, pause, and admire. My Egrets hung above a few 20 plants, my Long Otter looking over my Monstera, and my By the Lake print standing next to my propagation station, all got me thinking about the relationship between my green friends and visual arts.

Right away, a few greats came to mind: Vincent Van Gogh’s Still Life Vase with Twelve Sunflowers (1888) or Irises (1889) ; Monet’s Water Lilies — 250 paintings spread over 20+ years (late 1890s-1926) ; Matisse’s Sheaf (1953) ; and Andy Warhol’s Flowers (1970).

Monet is the one that took me on a journey. Although the lushness of the vegetation in Water Lily Pond, Green Harmony more references mediterranean gardens, the bridge’s shape influenced its name of “Japanese bridge” — and for this series, Monet found inspiration in his personal collection of Japanese prints. So let’s fly over to the East.

The Art of Nature

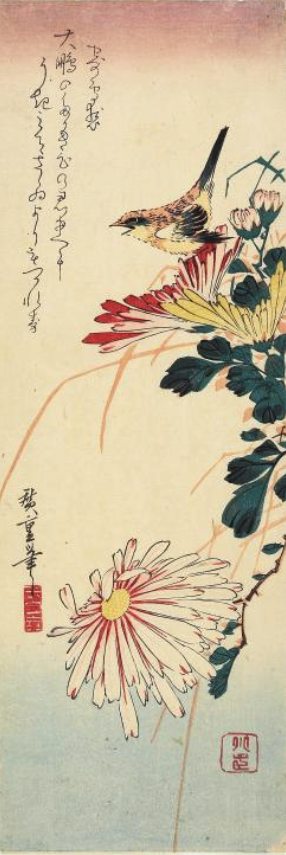

Now a source of inspiration to many, Japanese woodblock art prints first emerged in the 17th century. This technique had been around since the 8th century but was long used to reproduce foreign literature.

With Hokusai and Hiroshige being two of the most famous Japanese artists, a plethora of incredible landscapes and beautiful women were at the forefront, and so were Chrysanthemums , Peonies, Poppies, and many more.

%20Japanese%20Woodblock%20Reprint%20Pheasant%20and%20Chrysanthemum.jpeg?width=1200&length=1200&name=Hiroshige%20(1797%20-%201858)%20Japanese%20Woodblock%20Reprint%20Pheasant%20and%20Chrysanthemum.jpeg)

Japanese art and culture have long focused on nature. In Shintō, an ancient belief system, nature is revered as the home of local spirits called kami, which reside in plants, animals, and landscapes. Cultivating plants is considered an art form in itself and a source of tranquility. Japanese gardens use plants with unique looks and distinctive characteristics to evoke a metaphor for meditation.

Kokedama, also known as "moss ball," originated from bonsai, inspired by the beauty of exposed roots gathering moss, moss represents longevity, thriving gradually and blending harmoniously with its environment. Originally conceived to maintain a connection to nature in urban settings, these simple spheres are a fitting reflection of wabi-sabi, which roughly translates to finding beauty in natural imperfections. .

What leaves are made of

While exploring Japanese art, I was reminded of origami, which brings me to contemporary paper art. Friedrich Froebel (1782–1852), the German educator credited with inventing kindergarten, passionately advocated for the educational advantages of paper folding, significantly contributing to its spread across the world. Later on, the Bauhaus school of design used paper folding to train students in commercial design. After World War II, paper crafting became more and more popular in the United States.

I find it quite fitting that paper is made of trees and plants can be made of paper. Hot tip: they don’t die.

With her project Tiny Big House Plants, paper artist Raya Sader Bujana crafts minute houseplants, using folding, scoring, and wrapping to convey the shape and variegation in leaves.

Previously the director of special projects at the event design firm David Stark Design, Corrie Beth creates playful life-size paper plants, a series named Handmade Houseplants.

Marine Le Carrer, French paper artist, has created paper plants for brands such as Louis Vuitton and Dior, alongside perfume paper gardens and a large floral setting for the Paris Rhum Fest 2023.

Shooting plants

The ability to capture each moment with photography and the fleeting nature of botanical elements have remained intricately linked throughout history. At the dawn of photography, scientist Henry Fox Talbot emerged as a champion of both. An advocate for botanical studies, his pioneering experiments in documenting flora showed how valuable photography could be to botanists and scientists.

Anna Atkins, an English botanist who knew Talbot, developed “cameraless” photography as a medium for recording images of plants, leveraging cyanotypes (commonly known as blueprints). The cyan blue colour is caused by a chemical mix that reacts to light: Place a plant on a sheet of chemically treated paper, and watch it turn into a work of art.

-1.jpeg?width=281&height=370&name=Anna%20Atkins%2c%20Alaria%20esculenta%20(1849)-1.jpeg)

Anna Atkins, Alaria esculenta, 1849

Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932) was a sculptor turned photographer who captured close-up shots of plants. With a keen interest in botany, he used photography to illustrate botanical differences for teaching purposes. Developing specialized cameras, he achieved unprecedented magnified detail (up to x30) of plants and their textures. His first publication, "Urformen der Kunst" (Artforms in nature) (1929), showcased his black and white photogravure images after an exhibition in Berlin. Blossfeldt's collection comprises around 6,000 photographs, celebrated for their unique portrayal of plants' form and structure, inspiring many to emulate his style.

Leafy Legacy

Moss People by Kim Simonsson have become a fixture at Art Basel Miami, leading the viewer into a fairytale like world, inspired by the forests and folklore of his native Finland. Engineers such as ForgeCore have designed and created 3D printed plant coasters and toothpick holders in the shape of cacti, bringing extra utility to greenery. Contemporary tattoo designs that adorn our skins today often draw inspiration from simplified adaptations of Japanese woodblock prints.

Gamma Partner Artists aren’t immune to the charms of botanical beauties, and are bringing plants to the blockchain too. Let’s take a look at Bitcoin etchings featuring our leafy companions.

‘The plant must be valued as a totally artistic and architectural structure’

-Karl Blossfeldt