Party animals

Did you know? A group of peafowls is called a party — and they party with each other, but not with other species. Peahens, the females of the species, are mostly brown and white, and don’t have the colourful tail display that males use to attract them. As peahens get older and their oestrogens levels drop, they sometimes develop their own trains. For peacocks, it takes 3 years to grow their beautiful tails! When peacocks rattle their trains creating a rustling sound, the peahens also feel a vibration thanks to their crests, a resonant frequency that humans cannot feel. When mating season is over, peacocks naturally shed some of their 200 train feathers. Let’s take a look at how these majestic creatures have influenced the arts over the centuries.

Peacocks in the arts

Over the last few centuries, artists have used symbolism to convey messages with subtlety and nuance. While the symbol of the “eyed feathers” mean different things for different cultures, peacocks are no exception and have been used by many to represent royalty, beauty, rebirth, immortality, paradise, and wealth.

Originally from India, peacocks made their way to Western visual culture when the ancient Romans and Greeks started capturing their beauty in mosaics. They associated the eye-like shapes on peacock tails to the stars and thought of peacocks as a symbol for eternal life. In fact, they associated the creature with immortality because it seemed to be able to eat poison and survive. It is now believed that the bird’s ability to eat unusual foods fuels its colouration, a little like flamingos achieve pink feathers by eating volcanic algae. Blue is the rarest animal colour in the world, making peacocks all the more exceptional. Despite their fascination for the peacock’s incredible colours, the Romans and Greeks never quite managed to find an artistic expression for peacocks in the way they had with eagles and lions.

While most cultures give positive symbolism to the fantastic bird, peacocks have also been used in art and literature around the world as symbols of vanity and pride, thus the English phrase “proud as peacock” which originated in the 14th Century, if not earlier. Mainstream adoption of the peacock in visual arts wasn’t there yet.

Fast forward to the 19th Century Victorian colonial world. In 1876, painter James McNeill Whistler tried his hand at interior design in a private home in Chelsea, England. The bird made an impressive public appearance with the “Peacock Room”, which featured golden peacocks across petrol blue walls. The painter’s client famously hated the Peacock Room, and it was only 28 years before it was taken down and shipped to America. The artwork now stands at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington.

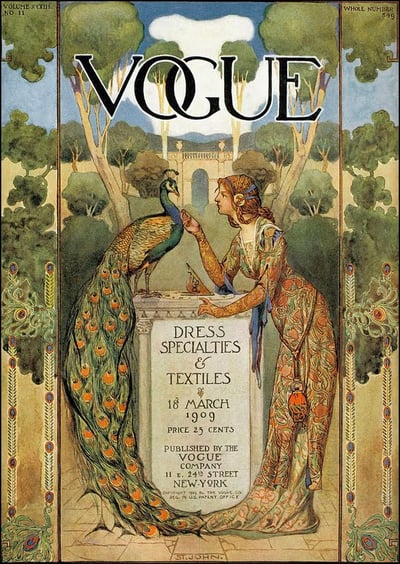

In 1887, the Liberty of London, one of London’s first department stores, named their newest pattern after the Greek goddess Hera, whose chariot was pulled by peacocks. Liberty’s peacock fabric is still reproduced and in Vogue to this day. Liberty would champion the Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau movements in Europe, with Italy first referring to Art Nouveau as the “Stile Liberty”.

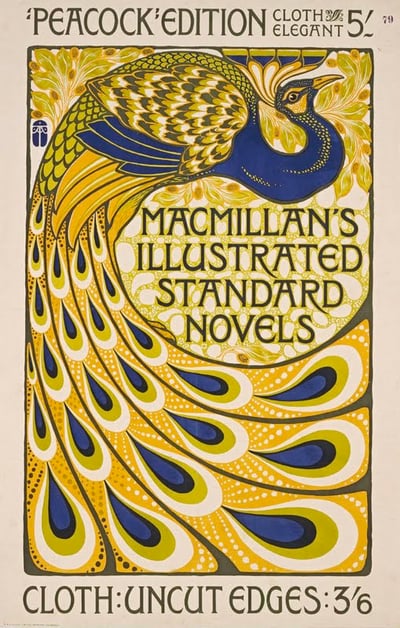

The British Arts & Crafts movement was the springboard for the subsequent Art Nouveau movement, and sought a new visual language based on natural forms. What could be better suited to intertwine with foliage designs than the swirling feather patterns of a peacock? It was not long before the colourful eyes and twirls adorned ball gowns, ceramics, and paintings, making their way into Victorian society.

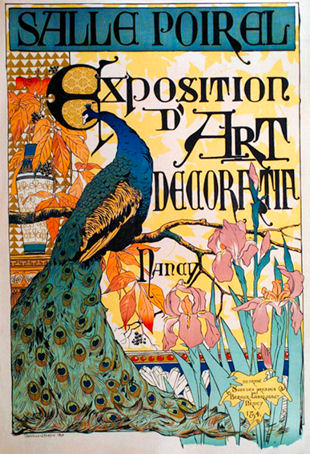

This bird was now in fashion and soon made its way across the Channel to become French Art Nouveau’s muse. Artists and designers were looking for something new — they were attracted to the curves and lines of nature’s flora and fauna, and the glamorous peacock was a perfect match for painting, architecture, ironwork, railings, fabrics, pendants, rings, brooches, and more. These artists had found an endless source of inspiration.

Next time you stop by the Châtelet or Abbesses metro stations in Paris, look up and observe Hector Guimard’s fabulous entrances in the shape of a peacock train. In New York, Louis Comfort Tiffany used coloured stained leaded-glass with peacock imagery to create translucent lampshades, and also created one of the world’s most famous doors at the Palmer House Hotel in Chicago.

It should be noted that white peacocks attracted the eye too: in 1898, Jean Delville’s “L’École de Platon” (Plato’s school) featured one. Although this specific representation of the bird referred to Plato’s gown and the idea of purity, white peacocks do exist. While very rare in nature, they are more common now because of selective breeding — they have leucism, which only affects the colouring of the feathers, leaving them with their black eyes. The piece is now exhibited at the Orsay Museum in Paris.

By the end of the 19th Century, peacocks were all over posters for events and exhibitions, fashion magazine covers, and book covers. They were everywhere.

The Art Nouveau and Belle Epoque era ended when WW1 started and by 1918, people were no longer interested in the movement. Despite the lost interest in Art Nouveau, the peacock lived on through fabric and fashion, with incredible patterned ball gowns taking over the world of cinema and theatre in the 20s.

In 1963, peacocks became the national bird of India, and sometime along the way, March 25th became international peacock day.

Cover photo by David Trinks